A 1948 flood washed away the WWII housing project Vanport—but its history still informs Portland’s diversity.

Natasha Geiling

February 18, 2015

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/vanport-oregon-how-countrys-largest-housing-project-vanished-day-180954040/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/author/natasha-geiling/

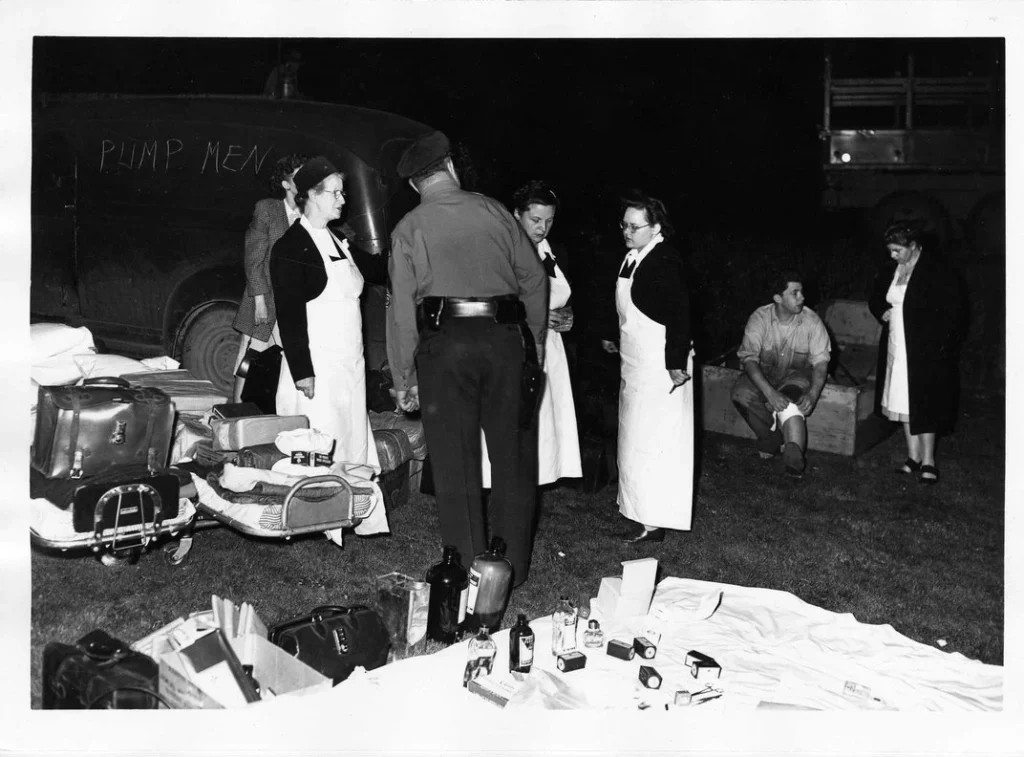

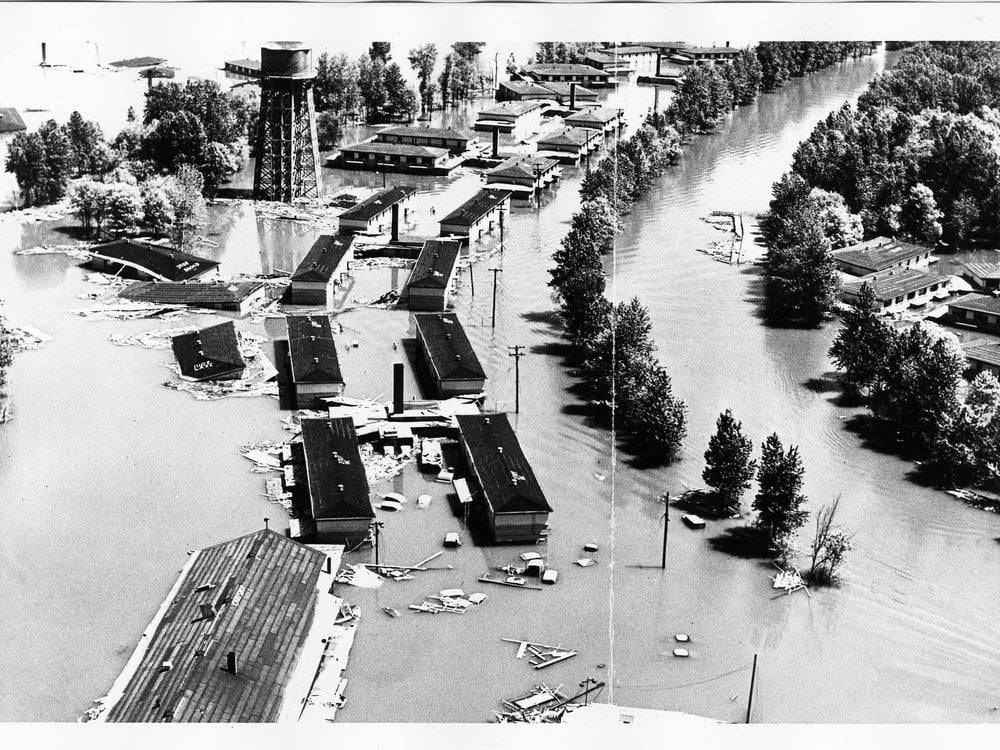

Buildings and trees are loosely spaced in arches, with debris floating in flood. Black and white.

The mere utterance of Vanport was known to send shivers down the spines of “well-bred” Portlanders. Not because of any ghost story, or any calamitous disaster—that would come later—but because of raw, unabashed racism. Built in 110 days in 1942, Vanport was always meant to be a temporary housing project, a superficial solution to Portland’s wartime housing shortage. At its height, Vanport housed 40,000 residents, making it the second largest city in Oregon, a home to the workers in Portland’s shipyards and their families.

But as America returned to peacetime and the shipyards shuttered, tens of thousands remained in the slipshod houses and apartments in Vanport, and by design, through discriminatory housing policy, many who stayed were African-American. In a city that before the war claimed fewer than 2,000 black residents, white Portland eyed Vanport suspiciously. In a few short years, Vanport went from being thought of as a wartime example of American innovation to a crime-laden slum.

A 1947 Oregon Journal investigation discussed the purported eyesore that Vanport had become, noting that except for the 20,000-some residents who still lived there, “To many Oregonians, Vanport has been undesirable because it is supposed to have a large colored population,” the article read. “Of the some 23,000 inhabitants, only slightly over 4,000 are colored residents. True, this is a high percentage per capita compared to other Northwestern cities. But, as one resident put it, the colored people have to live somewhere, and whether the Northwesterners like it or not, they are here to stay.”

Faced with an increasingly dilapidated town, the Housing Authority of Portland wanted to dismantle Vanport altogether. “The consensus of opinion seems to be, however, that as long as over 20,000 people can find no other place to go, Vanport will continue to operate whether Portland likes it or not,” the 1947 Sunday Journal article explained. “It is almost a physical impossibility to throw 20,000 people out on the street.”

Almost—but not, the city would soon learn, completely impossible.

***********

Delta Park, tucked along the Columbia River in Portland’s northern edge, is today a sprawling mix of public parks, nature preserves and sports complexes. Spread across 85 acres, it houses nine soccer fields, seven softball fields, a football field, an arboretum, a golf course and Portland’s International Raceway. It’s spaces like this—open, green and vibrant—that make Portland an attractive place to call home; recently, it was named one of the world’s most livable cities by the British magazine Monocle—the only U.S. city to make the list. In the park’s northwest corner sits Force Lake—once a haven for over 100 species of birds and a vibrant community swimming hole, now a polluted mess. Around the lake stand various signposts—the only physical reminder of Vanport City. But the intangible remnants of Vanport live on, a reminder of Portland’s lack of diversity both past and present.

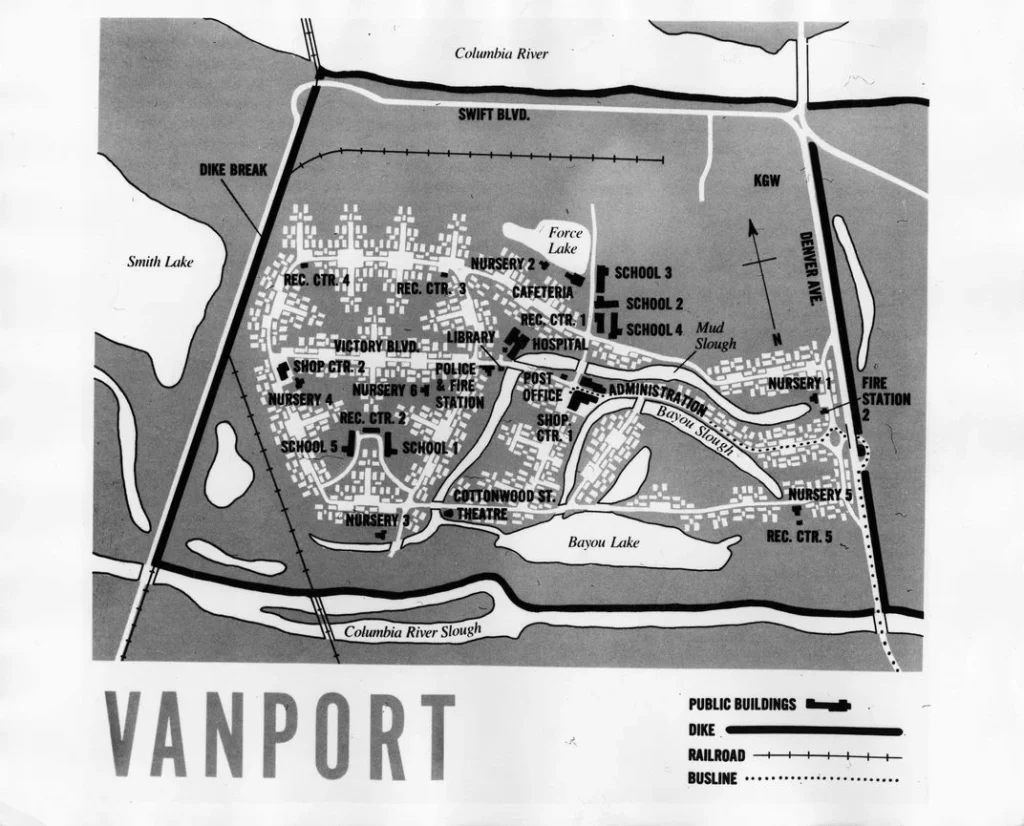

Old, professionally made map, black and white.

Portland’s whiteness is often treated more as joke than a blemish on its reputation, but its lack of diversity (in a city of some 600,000 residents, just 6 percent are black*) stems from its racist history, of which Vanport is an integral chapter. When Oregon was admitted to the United States in 1859, it was the only state whose state constitution explicitly forbade black people from living, working or owning property within its borders. Until 1926, it was illegal for black people to even move into the state. Its lack of diversity fed a vicious cycle: whites looking to escape the South after the end of the Civil War flocked to Oregon, which billed itself as a sort of pristine utopia, where land was plentiful and diversity was scarce. In the early 1900s, Oregon was a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity, boasting over 14,000 members (9,000 of whom lived in Portland). The Klan’s influence could be felt everywhere, from business to politics—the Klan was even successful in ousting a sitting governor in favor of a governor more of its choosing. It was commonplace for high-ranking members of local and statewide politics to meet with Klan members, who would advise them in matters of public policy.

In this whitewashed world, Portland—Oregon’s largest city then and now—was known as one of the most segregated cities north of the Mason-Dixon line: the law barring blacks from voting in the state wasn’t revoked until 1927. Most of Portland’s black residents before World War II had come to the city to work as railroad porters—one of the few jobs they were legally allowed to hold in the state—and took up residence in the area of Albina, within walking distance to Portland’s Union Station. As the Albina district became a center for black residents, it also became one of the only places in the city where they were allowed to live. Extreme housing discrimination, known as redlining, prohibited minorities from purchasing property in certain areas: in 1919, the Realty Board of Portland approved a Code of Ethics that forbade realtors and bankers from selling or giving loans for property located in white neighborhoods to minorities. By 1940, 1,100 of Portland’s 1,900 black residents lived in the Albina district centered around North Williams Avenue in an area just two miles long and one mile wide.

Like it did to so much of the country, World War II changed the landscape of Portland completely. In 1940, just before the United States entered into the war, industrialist Henry Kaiser struck a deal with the British Navy to build ships to bolster Britain’s war effort. Searching for a place to build his shipyard, Kaiser set his sights on Portland, where the newly opened Bonneville Dam offered factories an abundance of cheap electricity. Kaiser opened the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation in 1941, and it quickly became known as one of the most efficient shipbuilding operations in the country, capable of producing ships 75 percent faster than other shipyards, while using generally unskilled, but still unionized, laborers. When America entered the war in December of 1941, white male workers were drafted, plucked from the shipyard and sent overseas—and the burden of fulfilling the increased demand for ships with America’s entrance into the war fell to the shoulders of those who had otherwise been seen as unqualified for the job: women and minorities.

Black men and women began arriving to Portland by the thousands, increasing Portland’s black population tenfold in a matter of years. Between 1940 and 1950, the city’s black population increased more than any West Coast city other than Oakland and San Francisco. It was part of a demographic change seen in cities across America, as blacks left the South for the North and West in what became known as the Great Migration, or what Isabel Wilkerson, in her acclaimed history of the period, The Warmth of Other Suns, calls “the biggest underreported story of the 20th century.” From 1915 to 1960, nearly six million blacks left their Southern homes, seeking work and better opportunities in Northern cities, with nearly 1.5 million leaving in the 1940s, seduced by the call of WWII industries and jobs. Many seeking employment headed West, lured by the massive shipyards of the Pacific coast.

With Portland’s black population undergoing a rapid expansion, city officials could no longer ignore the question of housing: There simply wasn’t enough space in the redlined neighborhoods for the incoming black workers, and moreover, providing housing for defense workers was seen as a patriotic duty. But even with the overwhelming influx of workers, Portland’s discriminatory housing policies reigned supreme. Fearing that a permanent housing development would encourage black workers to remain in Oregon after the war, the Housing Authority of Portland (HAP) was slow to act. A 1942 article from the Oregonian, with the headline “New Negro Migrants Worry City” said new black workers were “taxing the housing facilities of the Albina District… and confronting authorities with a new housing problem.” Later that same year, Portland Mayor Earl Riley asserted that “Portland can absorb only a minimum number of Negros without upsetting the city’s regular life.” Eventually, the HAP built some 4,900 temporary housing units—for some 120,000 new workers. The new housing still wasn’t enough for Kaiser, however, who needed more space for the stream of workers flowing into his shipyards.

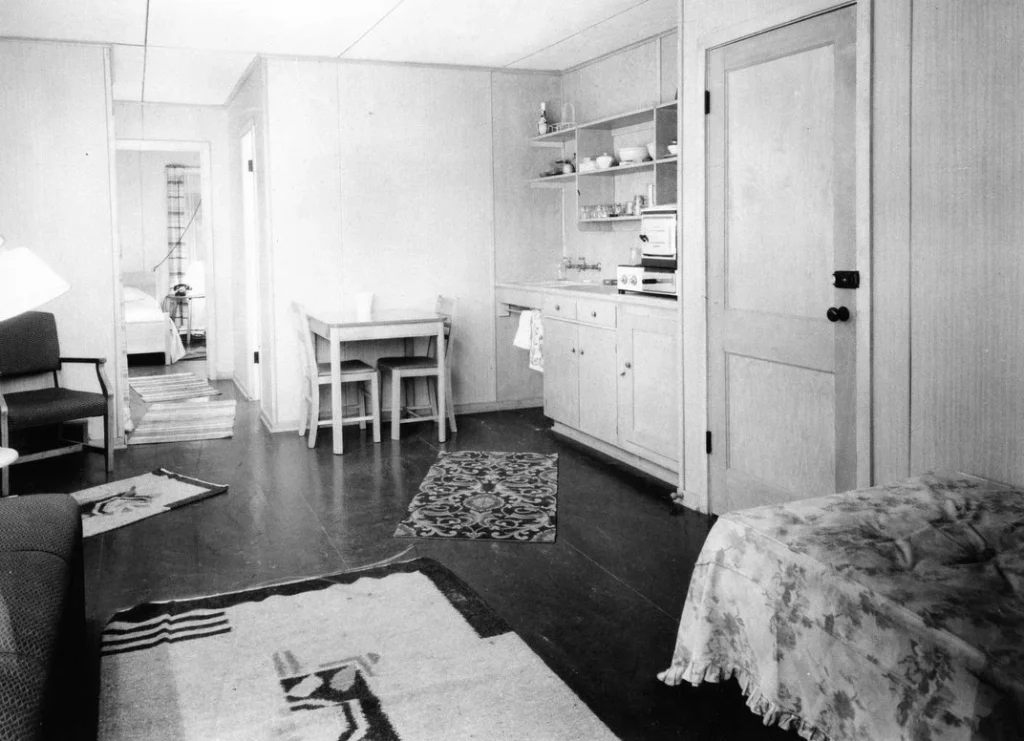

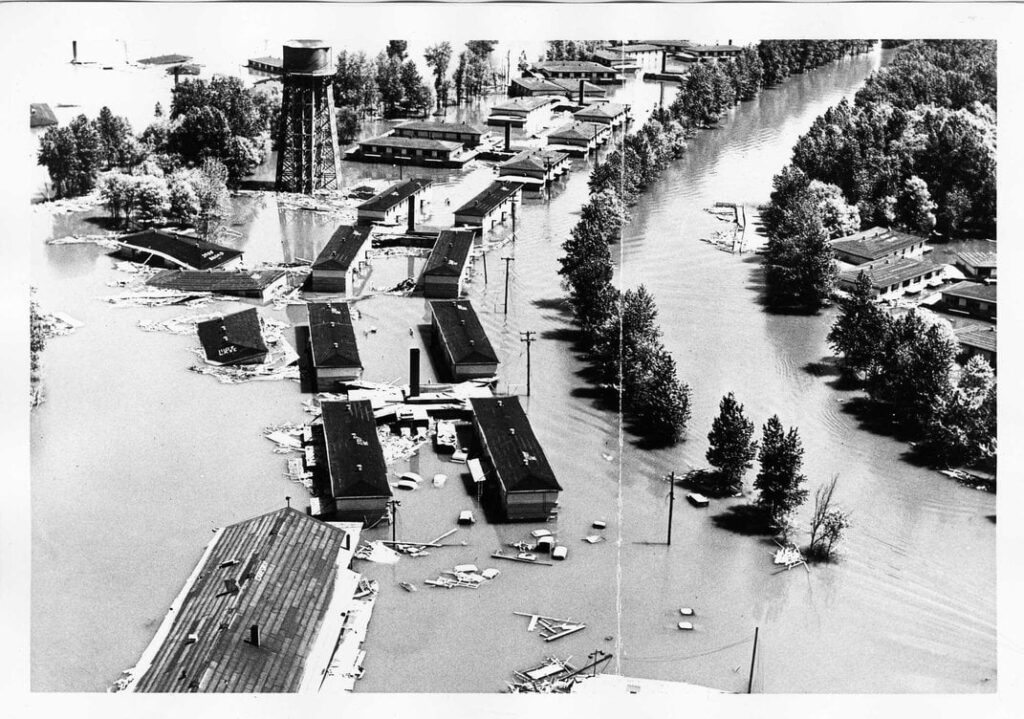

Kaiser couldn’t wait for the city to provide his workers with housing, so he went around officials to build his own temporary city with the help of the federal government. Completed in just 110 days, the town—comprised of 10,414 apartments and homes—was mostly a slipshod combination of wooden blocks and fiberboard walls. Built on marshland between the Columbia Slough and the Columbia River, Vanport was physically segregated from Portland—and kept dry only by a system of dikes that held back the flow of the Columbia River. “The psychological effect of living on the bottom of a relatively small area, diked on all sides to a height of 15 to 25 feet, was vaguely disturbing,” wrote Manly Maben in his 1987 book Vanport. “It was almost impossible to get a view of the horizon from anywhere in Vanport, at least on the ground or in the lower level apartments, and it was even difficult from upper levels.”

Seemingly overnight, Vanport (named because it was midway between Portland and Vancouver, Washington) became Oregon’s second biggest city and the largest housing project in the country, home to 40,000 workers at its peak (6,000 of whom were black). At its opening in August of 1943, the Oregonian heralded it as a symbol of America’s wartime ingenuity. “Vanport City goes beyond providing homes for defense workers,” the article proclaimed. “It is encouraging all possible conditions of normal living to parallel the hard terms of life in a war community.”

**********

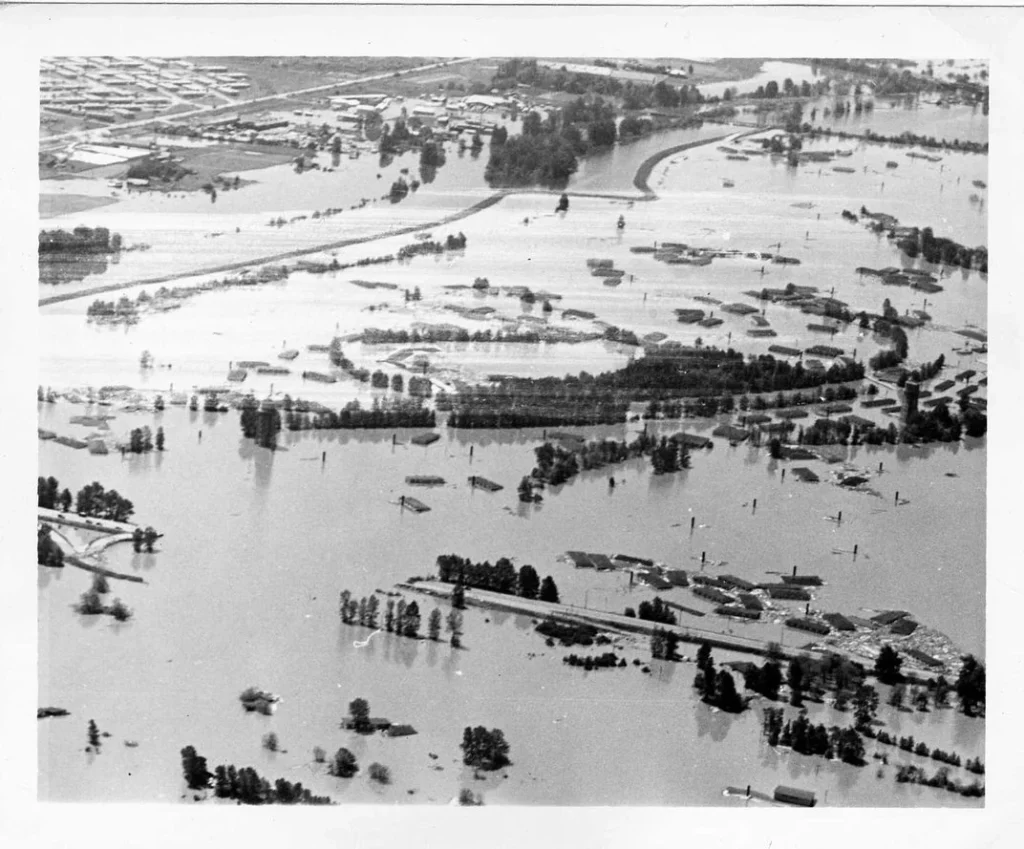

The year 1948 had been a particularly wet year, even by Oregon standards—a snowy winter had left the mountain snow pack bloated, and a warm, rainy May combined with the spring melt to raise the level of the Columbia River to dangerous heights. By May 25, 1948, both the Columbia and Willamette Rivers reached 23 feet, eight feet above flood stage. Officials in Vanport began patrolling the dikes that day, but didn’t issue any warnings to Vanport’s residents; the United States Army Corps of Engineers had assured the HAP that the dikes would hold, and that Vanport would remain dry in the face of increasingly rising waters. Still, the HAP safeguarded its files and equipment—removing them from their offices in Vanport, along with some 600 horses from the adjacent racetrack.

On May 30—Memorial Day, 1948—Vanport woke up to a flyer from the HAP that read:

REMEMBER.

DIKES ARE SAFE AT PRESENT.

YOU WILL BE WARNED IF NECESSARY.

YOU WILL HAVE TIME TO LEAVE.

DON’T GET EXCITED.

The dikes did not hold. At 4:17 p.m., a break came in a railroad dike that separated Vanport from Smith Lake, along the city’s northwest edge. What began as a small hole—just six feet, initially—rapidly expanded, until water was steadily streaming through a 500-foot gap in the dike. As water seeped into the city, homes were swept away in the flood, their foundationless-walls unable to withstand the force of the water. According to Rachel Dresbeck in her book Oregon Disasters: True Stories of Tragedy and Survival, it wasn’t the HAP or city police that first alerted residents to the incoming flood, but students and faculty from Vanport College, who had come to Vanport on a Sunday in order to collect and secure their research projects. Though the Columbia Slough succeeded in absorbing some of the incoming water, within ten minutes, Vanport was inundated. In less than a day, the nation’s largest housing project—and Oregon’s second largest city—was destroyed. 18,500 residents were displaced, and roughly 6,300 were black.

In the days following the Vanport flood, rumors swirled in the local press. “Official” estimates of casualties—doled out liberally to reporters by those not directly involved with the investigation—were in the hundreds, and eyewitness accounts told stories of dozens of bodies being carried down the Columbia River. Days into June, no bodies had been recovered from the flooded town, stoking rumors that the HAP had quietly disposed of bodies in order to lessen the blame for its mishandling of the situation. One news story suggested that the HAP had arranged for at least 600 bodies to be stored in the Terminal Ice & Cold Storage facility downtown; another story claimed that the governement had quietly and by the cover of night loaded 157 bodies (or 457, depending on the telling) onto a ship bound for Japan.

Most derided the rumors as “ugly” and “irresponsible,” and they were right, but they reflected the general distrust of the public—especially the now-displaced residents of Vanport—toward housing and city officials.

“If it had been a totally white population living there, would it have been different?” Ed Washington, once a resident of Vanport, speculates. “Probably. If they had been poor white people, would it have been different? Probably not.”

**********

Both black and white workers lived in Vanport, but unlike defense housing in Seattle, which was built in an integrated fashion, Vanport had been a segregated community, and the black workers were kept separate from the white workers. According to Vanport resident Beatrice Gilmore, who was 13 years old when her family moved from Louisiana (by way of Las Vegas) to Oregon, the segregation wasn’t mandated by law, but came as a result of practices from the HAP. “It wasn’t openly segregated,” Gilmore says. “The housing authority said it wasn’t segregated, but it was. There were certain streets that the African Americans were assigned to.”

For Gilmore, living in Vanport as a black teenager was more complicated than it had been in Louisiana: in the South, she explains, racism was so blatant that clear lines kept races apart. In Portland, racism was more hidden—black residents wouldn’t necessarily know if they were going to encounter discrimination in a business until they entered. “[Discrimination] was open in some areas and undercover in some areas, but it was all over,” she remembers.

Ed Washington was 7 years old when he moved from Birmingham, Alabama with his mother and siblings to join their father in Vanport. Washington says that he moved to Portland without the expectation of being treated any differently in the Pacific Northwest than he was in the South, though he recalls his father telling him that he would, for the first time, be attending school alongside white children, and that his family wouldn’t have to ride at the back of the bus.

“There were some of those vestiges [in Portland] also, and you learn that once you get here and once you start moving through the environment,” Washington recalls. In Vanport, Washington remembers encountering more racist remarks than as a child in Birmingham, simply because in Birmingham, blacks and whites rarely interacted at all. “In Birmingham, you lived in a black neighborhood, period. The incidents were much more heightened in Vanport, but I think those incidents were only initial, when people first started moving in. In Portland, there were far more incidents than I experienced in Birmingham.”

Despite offering residents an integrated education and community centers, life in Vanport wasn’t easy: Separated from Portland, miles to the nearest bus line, it was sometimes difficult to obtain daily necessities. By the winter of 1943-44, residents were moving out by as many as 100 a day—but not black residents, who, doomed by Portland’s discriminatory housing policies, had nowhere else to go. When the war ended in 1945, the population of Vanport drastically contracted—from a peak of 40,000 to some 18,500—as white workers left the city. Approximately one-third of the residents of Vanport at the time of the flood were black, forced to remain in the deteriorating city due to high levels of post-WWII unemployment and continued redlining of Portland neighborhoods.

“A lot of people think of Vanport as a black city, but it wasn’t. It was just a place where blacks could live, so it had a large population,” Washington explains. But in a place as white as Portland, a city that was one-third black was a terrifying prospect for the white majority. “It scared the crud out of Portland,” Washington says.

**********

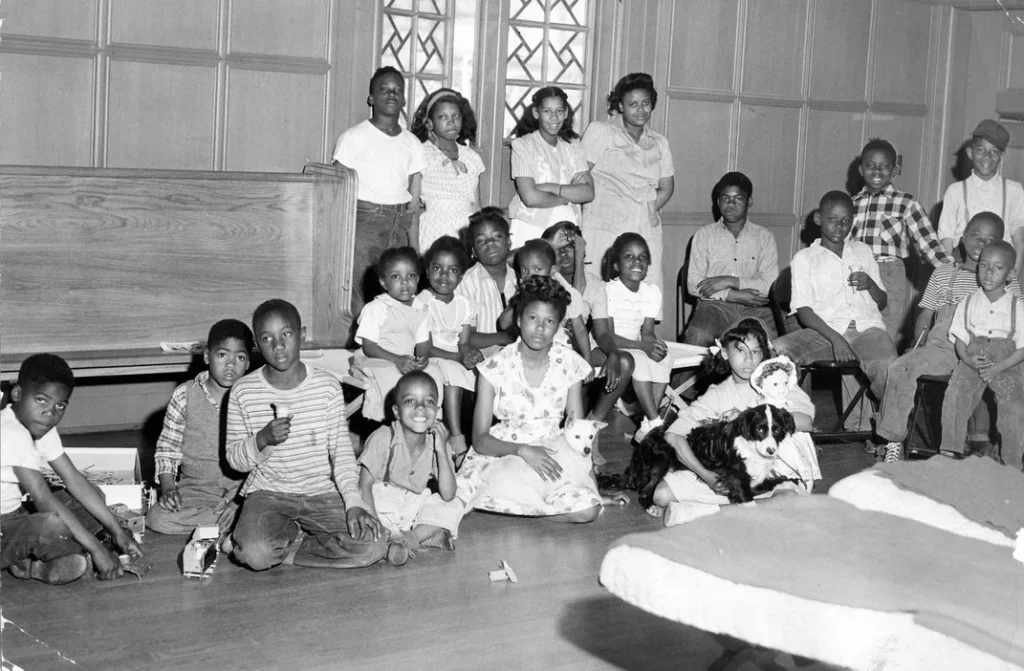

In total, 15 people perished in the Vanport flood, a number kept low by the fact that the flood occurred on a particularly nice Sunday afternoon, when many families had already left their homes to enjoy the weather. Temporarily, the line of racial discrimination in Portland was bridged when white families offered to take in black families displaced by the storm—but before long, the racial lines that existed before the flood hardened yet again. The total number of displaced black residents was roughly equal to the entire population of Albina, making it impossible for displaced black families to crowd into the only areas they were allowed to buy homes. Many—like Washington’s family—ended up back in temporary defense housing.

It would take some families years to find permanent housing in Portland—and for those who remained, the only option was the already overcrowded Albina district. According to Karen Gibson, associate professor of urban studies and planning at Portland State University, “The flood that washed away Vanport did not solve the housing problem—it swept in the final phase of ‘ghetto building’ in the central city.”

By the 1960s, four out of five black Portlanders lived in Albina—an area that would suffer years of disinvestment and backhanded home lending practices by city officials. By the 1980s, the median value for a home in Albina was 58 percent below the city’s average, and the neighborhood became best known as a hotbed of gang violence and drug dealing.

“The realty board controlled where people could live, and they were very strong and powerful in Portland,” Gibson says. “Those that [Portland officials] couldn’t discourage from staying [after the flood] were not going to be able to live anywhere other than where they had been designated to live, and that was the Albina district.” From the Albina district—which now encompasses seven neighborhoods in northeast Portland—have sprung famous black Portlanders, from jazz drummer Mel Brown to former NBA player Damon Stoudamire. Today, bolstered by economic interest in the area, Albina is undergoing the same kind of gentrification seen throughout economically depressed neighborhoods across America. With gentrification comes changes in a neighborhood’s fiber: once the cultural heart of black Portland, 54 percent of the neighborhood along North Williams Avenue, the main drag, is now white.

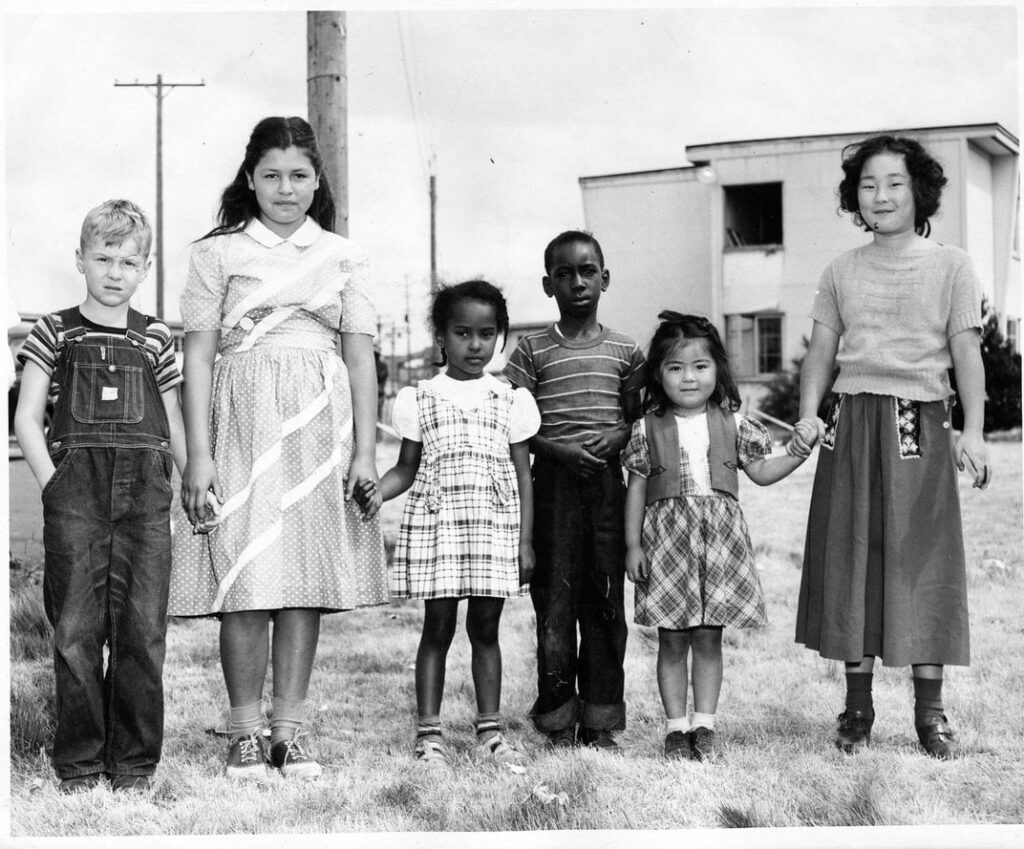

Sixty-seven years after Vanport, Portland is still one of the nation’s least diverse cities—the 2010 census shows diversity in the city’s center is actually on the decline. But Vanport’s legacy also remains in the brief integration that it forced, in its schools and community centers, for a generation of Americans that hadn’t experienced life in close proximity to another race.

Vanport schools were the first in the state of Oregon to hire black teachers, and they remained integrated against the wishes of the HAP. “I think the key to Vanport, for the kids, was the schools. The schools were absolutely outstanding,” Washington says. “A lot of African-American kids who went on to do some good things in their life, for a lot of them, myself included, it started with the schools in Vanport.”

Gilmore also found support in Vanport’s classrooms. “The teachers seemed to be interested in the students,” she says. “There were teachers that really understood the African American student’s plight, and they helped us. It was so open that you could study whatever you wanted, and I just loved it.”

Washington and Gilmore are both still Portland residents. Washington, now semi-retired, works as a community liaison for diversity initiatives at Portland State University four hours a day, four days a week, to “keep [his] mind fresh.” In 1955, Gilmore became the first African-American in the state to graduate from the Oregon Health and Science University nursing school; in addition to nursing, she’s dedicated her life to political and community concerns, promoting unity between races. She found the inspiration to do both, she says, in Vanport.

—

Through June 28, 2015, the Oregon Historical Society will be hosting the exhibit “A Community on the Move,” which explores the history of Vanport, as well as Portland’s black community throughout the 1940s and 50s. Curated by the Oregon Black Pioneers, the exhibition will feature a series of special community conversations, led by leaders and elders in Oregon’s black community. For more information on the exhibit, or to find a schedule of the offered talks, visit the exhibition website.

*This sentence previously misstated that Portland is 2 percent black; the state of Oregon is 2 percent black, while the city is 6.3 percent.